Water, Sovereignty, and the Politics of Blame: Reframing Syria’s Food Security Debate

In the Syrian case, neo-colonialism operates less through direct territorial control and more through structural dependence: control over finance, technology, narratives, and access to water flows (upstream, institutional, or humanitarian). Water governance becomes a lever that constrains food sovereignty while appearing technocratic, humanitarian, or environmentally neutral.

Introduction: from hydro-mission to a politics of legitimacy

Syria’s water story is routinely told as a linear cautionary tale: the state pursued wheat self-sufficiency, expanded irrigation beyond hydrological limits, depleted groundwater, and set the stage for crisis. The problem with this framing is not its empirical core (groundwater depletion, salinization, and pollution were real) but its politics of causality.

Few policy objectives have traveled as abruptly from virtue to liability as food security in Syria. Once framed as a cornerstone of sovereignty and social stability, food self-sufficiency is now frequently cited as the "cause" of water depletion, ecological collapse, and even conflict. This shift matters. It does not deny that water mismanagement occurred; on the contrary, it takes that reality seriously. What it questions is how causality has been narrated: how a critique of how food security was pursued was transformed into a judgment about whether it should be pursued at all. This piece argues that this transformation reflects a process of causal inversion that enables conceptual colonization, the external disciplining of food sovereignty through language, metrics, and governance norms. Through repetition, translation, and institutional uptake, food security shifted from being pursued imperfectly to being framed as inherently destabilizing. This inversion enables what can be described as conceptual colonization: the external restructuring of how food sovereignty is defined, evaluated, and conditionally legitimized.

The hydro-mission: building food security through water (1950–2000s)

From the mid-20th century onward, Syria pursued a classic hydro-mission: a state-led developmental phase in which large-scale water mobilization (dams, irrigation networks, reservoirs, pumping) was used to secure food production, integrate peripheral territories, and stabilize political authority. Hydro-missions are historically normal; they precede ecological regulation and integrated management rather than embody them.

Syria’s sequencing is well known.

The 1950s–1960s saw early flagship schemes such as Al-Ghab in the Orontes basin, supported by dams like Rastan (1960) and Mouhardeh (1961), and aligned with agrarian reform and central planning. The 1970s scaled the project dramatically through the Euphrates Valley Project, with Tabqa Dam (1973) and Lake Assad as its emblem. The aim was not only hydropower and irrigation expansion, but territorial integration: resettlement, planned villages, and state farms in the Jazira. By the 1990s, Syria had built a dense hydraulic portfolio across basins and expanded irrigated area substantially, with strategic cropping embedded in a procurement regime and fixed-price state buying.

The hydro-mission produced tangible gains (including periods of near wheat self-sufficiency) while simultaneously institutionalizing a legitimacy model centered on visible production outputs. Production became both the metric of success and the basis of political authority.

This visibility mattered. When ecological stress later accumulated, the same visibility made the production model vulnerable to reinterpretation. The infrastructure did not “cause” mismanagement; it enabled a political economy that prioritized production stability and political legitimacy, often at the expense of hydrological limits.

Groundwater: the quiet engine of “success,” and the saturation point (late 1990s–2010)

The decisive turn was not another dam.

It was the explosion of wells. As surface schemes reached operational limits, farmers increasingly relied on groundwater, facilitated by rural electrification, cheap diesel, and permissive enforcement. Well numbers expanded sharply, including many unlicensed wells, and groundwater-fed irrigation grew to match or exceed surface irrigation in key regions. This shift altered the hydro-mission’s character: from visible, centralized infrastructure to dispersed, privately managed abstraction.

Rivers lost baseflow; tributaries such as the Khabur and Balikh declined sharply; salinity and pollution intensified. Groundwater decline introduced a new element: measurability. Unlike gradual soil degradation, falling water tables are quantifiable. They generate technical diagnostics, satellite evidence, and basin-level assessments. Material stress became epistemically legible.

Institutional recognition came late.

Water Law 31 (2005) and basin-level committees signaled awareness of an approaching supply frontier, but enforcement capacity remained weak in a fragmented legal and administrative environment. When drought hit (2006–2010), depleted aquifers could not buffer it. By 2010, Syria’s agrarian model (built on production guarantees and hydraulic expansion) showed structural fragility.

Up to this point, the causal chain remains straightforward: water-intensive instruments contributed to groundwater depletion and ecological stress.The analytical rupture occurs when this chain is reorganized—when the instruments used to pursue food security are reframed as evidence that food security itself was conceptually flawed.

From Structural Vulnerability to Narrative Restructuring

Hydro-missions create both capacity and exposure. By centralizing legitimacy around production metrics and hydraulic expansion, they render policy objectives highly visible. When stress emerges, visibility enables attribution.

Material water stress alone does not produce delegitimation. It produces diagnostic clarity. What transforms diagnosis into conceptual reclassification is the interpretive frame within which those diagnostics circulate.

By the late 1990s and 2000s, groundwater depletion coincided with expanding global sustainability norms, integrated water management discourse, and comparative benchmarking frameworks. Under these conditions, environmental stress was not interpreted as a transitional phase of irrigation-state evolution, but as evidence of structural overreach.

The sequencing gap (expansion preceding environmental regulation) was common historically. What differed was the political and financial context in which Syria reached its ecological saturation point: fiscal pressure, transboundary asymmetries, donor engagement, and institutional fragmentation. These conditions made narrative restructuring plausible.

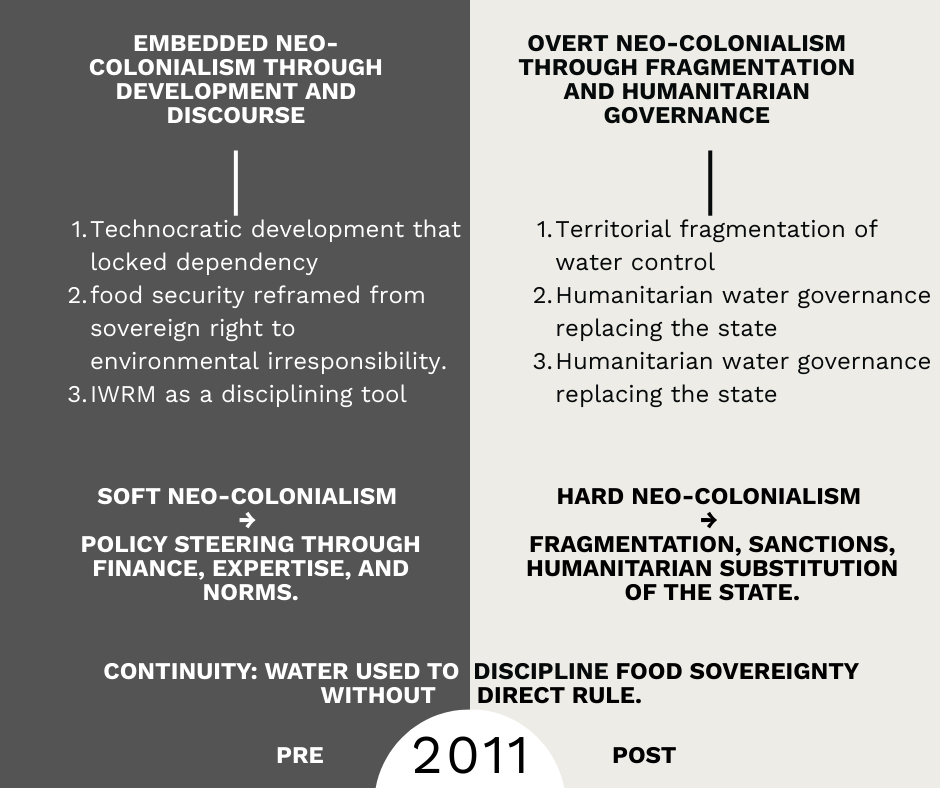

Neo-colonial dynamics in two phases

What does it mean to say food security was “colonized”?

Here, colonization does not mean food security was invented/imposed externally. It means its definition, evaluation criteria, and legitimacy became externalized; judged through frameworks that de-historicized Syria’s political economy, ignored transboundary hydropolitics, and applied asymmetric standards relative to Global North cases.

I: Pre-2011 (≈1980s–2011): embedded neo-colonialism through development and discourse

1) Large-scale irrigation and dam projects (especially Euphrates-linked systems) were promoted as food-security solutions but relied on external financing, expertise, and imported inputs. Even where sovereignty appeared hydraulic( big dams, big canals) policy autonomy was narrowed by the models embedded in project design: efficiency benchmarks, preferred modernization pathways, and investment priorities.

2) From the late 1990s, over-irrigation and groundwater depletion were increasingly framed as governance failure. Yet comparable water-intensive food systems in the US/EU were normalized as “transition costs,” while Syria’s were pathologized as evidence of irrational self-sufficiency. Critique often underweighted basin politics and upstream control, and over-weighted internal “misaligned incentives.” Thus, food security shifts from sovereign right to environmental irresponsibility.

3) IWRM language entered reforms post-2000, often via donor-driven pilots. Pricing, efficiency, and institutional “modernization” frequently preceded social safeguards. Adjustment costs (energy and water price exposure, reduced access to pumping) fell on small farmers, weakening the distributive foundations of state legitimacy in food provisioning.

II. Post-2011 (2011–present): overt neo-colonialism through fragmentation and humanitarian governance

1) Water infrastructure and authority fractured across regime areas, opposition-held zones, Kurdish-led territories, and extremist control. Irrigation and production collapsed where water access became militarized or externally mediated. Damage to canals, pumping stations, and energy supply compounded scarcity. The effects is a loss of a unified national water–food system. Fragmentation reduced the state’s capacity to coordinate production, regulation, and distribution at basin scale.

2) WASH and irrigation support increasingly moved through NGOs and UN clusters, bypassing national institutions. Water trucking and emergency borehole rehabilitation kept households alive, but did not restore productive agricultural systems at scale, while entrenching operational dependency.

3) Sanctions and financial strangulation (constraints on fuel, spare parts, banking, and finance) indirectly crippled irrigation and food production. Yet the resulting failures were frequently narrated as “technical collapse” rather than as compliance effects and procurement chokepoints, another form of neo-colonial mechanism: economic instruments producing ecological outcomes without formal control.

Often, food insecurity was repeatedly attributed to “regime mismanagement” or sometimes "drought" without equivalent scrutiny of sanctions, upstream hydropolitics, or conflict-era infrastructure targeting.

This is where the concept of conceptual colonization of food security becomes analytically precise:

- Soft phase (≈2000–2011): food security remains “allowed,” but only if redefined through external metrics; critique is disciplining rather than reformist.

- Hard phase (post-2011): food security is humanitarianized, reduced to caloric access and emergency aid; severed from domestic production, and implicitly tied to authoritarian failure and ecological collapse.

Mismanagement is not the colonized element. Food security is. Environmental degradation becomes the justification through which sovereignty over food systems is retracted and replaced by conditional governance.

Causal inversion: when food security becomes the explanatory variable

This is the conceptual hinge.

What followed, however, was a discursive shift. Increasingly, policy reviews, academic analyses, and international diagnostics reframed the relationship as:

food security itself → causes water failure.

This inversion matters because it redefines the solution.

If mismanagement is the problem, reform remains possible: crop reallocation, pricing, enforcement, energy reform, and conjunctive use. If food security is the problem, the remedy becomes constraint: reduced domestic production ambition, normalised import dependence, and suspicion toward state provisioning as such.

let us take the work Myriam Ababsa. Her research meticulously documents Syria’s agrarian trajectory: wheat self-sufficiency achieved through a combination of state irrigation schemes and rapidly expanding private groundwater use; the resulting depletion of aquifers in the northeast; and the vulnerability created by unregulated abstraction. These findings are not in dispute and have been widely cited across academic and policy literatures.

Crucially, Ababsa’s analysis diagnoses water mismanagement as a consequence of the instruments used to pursue food security, not as proof that food security itself was conceptually misguided. The distinction between objective and means is clear in her work. That distinction, however, becomes less stable as her findings travel.

When evidence travels: from diagnosis to causal inversion

As Ababsa’s empirical insights are absorbed into climate-conflict and food-security policy reports, a subtle but consequential linguistic shift appears. Critiques initially aimed at irrigation practices and regulatory failures are progressively reworded as critiques of food self-sufficiency itself. Language moves from “unsustainable irrigation practices undermined water resources” to formulations such as “the pursuit of food self-sufficiency drove groundwater depletion.”

This is not merely stylistic. It collapses the distinction between policy instruments and policy goals. Multi-scalar constraints (drought variability, upstream hydropolitics, capital scarcity, sanctions, and sequencing limits) fade into the background. Food security becomes the proximate causal agent. What began as a reformable governance failure is reframed as a conceptual error.

This causal inversion does not accuse actors of bad faith. It emerges through repetition, summary, and translation across disciplines and institutions. Yet its effects are profound.

Let us see here:

“Environmental degradation was a key legacy of Syria’s bid for food self-sufficiency in the 1980s and 1990s. … groundwater and soil resources … were exhausted in the process.”

Sowing Scarcity: Syria’s Wheat Regime from Self-Sufficiency to Import-Dependency, citing Ababsa.

or:

“In a bid to establish food self-sufficiency, the Syrian state developed extensive irrigation projects and provided direct wheat subsidies and indirect water subsidies to intensify wheat production.”

Sowing Scarcity, paraphrasing Ababsa’s chapter.

"This was in the context of an expansive Syrian government agriculture policy to attain ‘food security’ and self-sufficiency in key crops,which led to over-exploitation of ground water in the following decades."

Water Scarcity, Mismanagement and Pollution in Syria

The inversion that recasts food self-sufficiency from a sovereign objective pursued through flawed instruments into the causal origin of ecological collapse performs a colonizing function: it decontextualizes policy choices, reallocates authority to external governance regimes, and transforms environmental accountability into a disciplinary judgment that renders food sovereignty revocable.

Conclusion: reclaiming causality without absolution

Syria’s hydro-mission produced both gains and degradation. The central claim of this article is not that mismanagement did not occur, but that the interpretation of mismanagement underwent a structural shift.

A distinction must therefore be maintained:

- Material degradation resulted from water-intensive instruments operating under fiscal, institutional, and transboundary constraints.

- Conceptual delegitimation emerged when those instruments were collapsed into the objective of food security itself.

The move from “reform instruments” to “constrain objectives” marks the analytical transformation examined here.

When food security is reframed as the causal origin of ecological failure, policy space contracts. Domestic production ambition becomes suspect. External governance appears neutral and corrective. Authority over water–food systems becomes conditional on compliance with externally defined sustainability metrics.

Conceptual colonization does not deny environmental stress. It restructures how that stress is interpreted and who is authorized to define legitimate responses.

Recognizing this distinction has concrete implications:

- Re-politicize the water–food nexus by restoring the analytical separation between instruments and objectives.

- Incorporate upstream hydropolitics and sanctions-induced constraints explicitly into viability assessments of irrigated recovery.

- Shift post-conflict governance from emergency provisioning toward reconstruction of productive water systems.

- Reframe environmental critique as contextual and reform-oriented rather than as categorical delegitimation.

The objective is not absolution. It is analytical precision. Mismanagement is corrigible. Delegitimation restructures sovereignty. Confusing the two transforms technical reform into structural conditionality.