Cropland Data Uncertainty Is a Food-Security Risk: Syria as a Case Study

How much cropland does Syria actually have?

At first glance, this may seem like a technical or academic question. In reality, it is a policy problem with real consequences. Governments, humanitarian agencies, and development partners rely on cropland estimates to assess food security risks, plan agricultural recovery, allocate water, and anticipate shocks. When those estimates are uncertain (or contradictory) policy decisions are made on unstable ground.

Syria offers a clear and cautionary example.

Two “authoritative” datasets, two different stories

Croplands (defined as arable land and permanent crops) cover more than 1.5 billion hectares worldwide and are central to feeding a projected 9.3 billion people by mid-century, according to Food and Agriculture Organization. Because of this, cropland extent is often treated as a foundational statistic in food security assessments, agricultural investment planning, and climate adaptation strategies.

Yet cropland data is rarely discussed in terms of uncertainty. Syria demonstrates why this silence matters.

At the national level, two data sources are commonly used to describe cropland extent:

- Satellite-derived land cover maps, such as the European Space Agency (ESA) Climate Change Initiative Land Cover (ESA CCI-LC), which offer globally consistent, annual maps derived from Earth observation data. Their main strength lies in long-term consistency, which allows users to examine trends over decades.

- Official agricultural statistics, such as FAOSTAT, which compile official agricultural statistics reported by national authorities, including areas under arable land and permanent crops. These data are deeply embedded in policy workflows and international reporting systems.

FAO cropland data do not operate in isolation. They are widely used as a baseline input by numerous downstream platforms, including global food-security monitoring systems, humanitarian early-warning tools, academic datasets, and development planning models. As a result, any uncertainty or methodological limitation embedded in FAO estimates is often inherited (implicitly and uncritically) by other platforms that rely on them for calibration, validation, or gap-filling. In conflict-affected contexts such as Syria, this cascading reliance amplifies the risk that a single uncertain estimate becomes normalized across multiple decision-making systems, reinforcing a false sense of precision rather than prompting scrutiny.

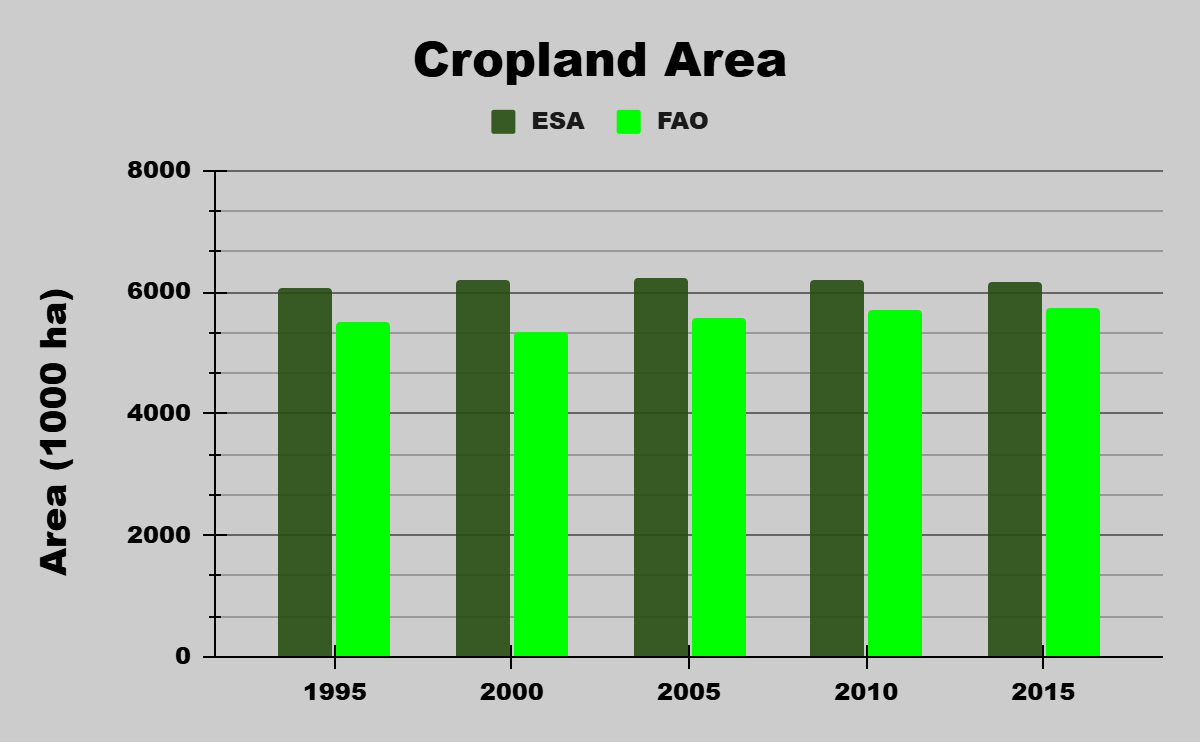

Both datasets are widely cited. Both are considered credible. And yet, when applied to Syria over the same period, they do not tell the same story.

Syria spans multiple climatic zones, from Mediterranean coastal areas to semi-arid central regions and arid eastern deserts. Prior to the conflict, agriculture played a vital role in livelihoods and exports, relied heavily on rain-fed production, and accounted for the majority of national water use. This combination of climatic sensitivity and socio-economic importance makes cropland data particularly consequential.

It also makes Syria a stress test for data systems.

Across overlapping years, FAOSTAT consistently reports lower cropland areas than those derived from ESA CCI-LC. In some years, the divergence is modest; in others, it is substantial. More importantly, the temporal trends do not align well, meaning the two sources often disagree not only on how much cropland exists, but also on whether it is increasing, decreasing, or stabilizing.

Periods of drought and the years following the onset of armed conflict coincide with increased divergence between the two sources. This suggests that both biophysical stress and institutional disruption influence not only agricultural outcomes, but also how those outcomes are measured and reported.

For policy users, this creates a fundamental problem: which number should be trusted?

Why disagreement is not a technical failure, but a governance risk

The discrepancy is not simply a matter of “good” versus “bad” data. It reflects structural differences in how cropland is defined and measured.

On the satellite side:

- Mixed landscapes dominate much of Syria’s agricultural regions, especially rain-fed zones. At moderate spatial resolution, cropland is often interwoven with natural vegetation, leading to under- or over-representation depending on classification choices.

- Mosaic land-cover classes introduce ambiguity: should partially cultivated pixels count fully as cropland, partially, or not at all?

On the statistical side:

- FAOSTAT relies on national reporting systems that were already under strain before 2011 and have been severely disrupted since.

- During conflict, reporting consistency, verification, and methodological continuity become difficult, even when institutions continue to publish figures.

Individually, these limitations are manageable. Collectively, they create uncertainty that is rarely communicated to policy users, who often see single cropland figures presented as objective facts.

Why this matters for food security policy

Cropland extent is not an abstract indicator. It feeds directly into food-balance calculations, early warning systems, irrigation planning, post-conflict recovery strategies, and climate adaptation frameworks. When cropland estimates are assumed to be precise rather than uncertain, policies risk being built on fragile foundations.

Overestimating cropland can mask production shortfalls. Underestimating it can delay investment or recovery support. In both cases, uncertainty (when left implicit) becomes a vulnerability.

In a country like Syria (where drought, conflict, displacement, and institutional fragmentation intersect) data uncertainty compounds vulnerability. Decisions made on uncertain baselines can amplify risk rather than reduce it.

A key lesson from Syria: uncertainty must be explicit

The most important takeaway from comparing satellite-based cropland maps with official statistics is not which dataset is “right.” It is that cropland estimates should be treated as ranges, not single values, especially in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

For policy and planning purposes, this implies several shifts:

- Acknowledge uncertainty openly

Cropland figures should be accompanied by uncertainty bounds or scenario ranges, rather than presented as precise numbers. - Use multiple data sources in parallel

Satellite products and national statistics should be seen as complementary, each highlighting different dimensions of reality. - Avoid over-interpreting short-term fluctuations

Apparent year-to-year changes may reflect reporting or classification artefacts rather than real land-use change. - Invest in hybrid approaches

Combining remote sensing, targeted field validation, and sub-national reporting can substantially improve confidence where it matters most.

Looking ahead: from data comparison to better decisions

Syria’s case illustrates a broader issue relevant far beyond its borders. As food security planning increasingly relies on global datasets, the gap between data producers and data users becomes a policy risk in itself.

Better decisions do not require perfect data. They require:

- transparent assumptions,

- explicit uncertainty,

- and an understanding of what different datasets can (and cannot) reliably say.

In fragile contexts, treating cropland data as unquestionable truth is no longer defensible. Treating it as evidence with limits is not a weakness, it is the foundation of responsible policy.

This topic remains open to further analytical, methodological, and collaborative work. Future research could focus on systematically comparing global agricultural datasets in conflict-affected settings, developing uncertainty-aware indicators for food security planning, and co-producing alternative cropland estimates with local experts where institutional data gaps persist. There is particular scope for interdisciplinary collaboration between remote sensing specialists, agricultural economists, and policy practitioners to ensure that cropland data used in humanitarian and recovery planning are both transparent and context-sensitive.