Syria: From reactive to proactive drought management

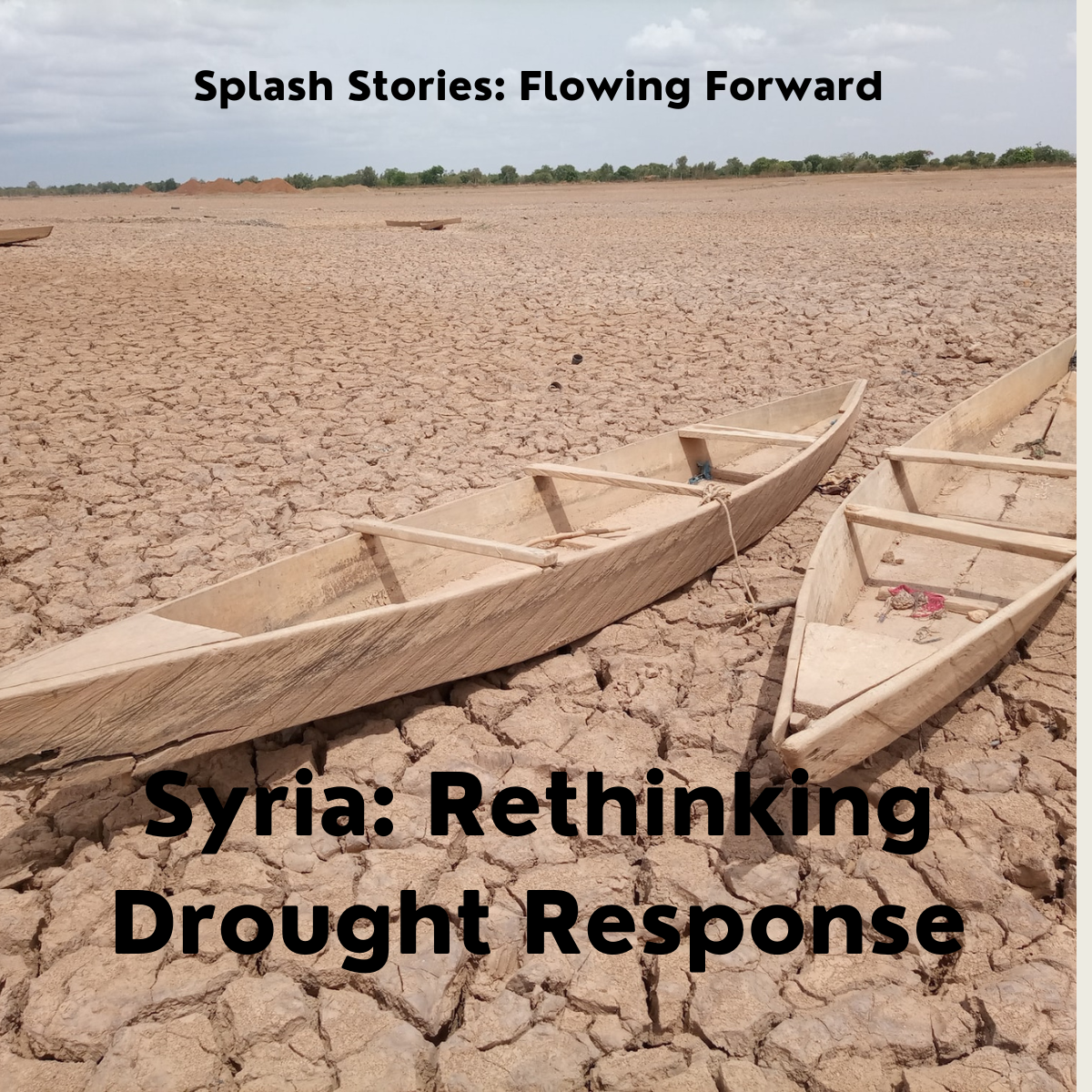

Drought in Syria, a looming crisis!

Human-induced climate change, which caused acute drought in Syria and large-scale migration and displacement, exacerbated the already unstable socio-economic circumstances and increased civil unrest in Syria. During the 1980s, Syria has been ravaged by three significant droughts, the most recent of which occurred between the years 2006 and 2010 and is regarded by many as the worst multi-year drought in recent history [1].

Former US President Barack Obama [2], Democratic presidential candidates Martin O'Malley [3] and Bernie Sanders [4], and UK, back then, Prince Charles have all claimed that a prolonged drought was a major hidden contributor to the Syrian conflict [5]. Reports by international organizations and NGOs [6]; and academics (e.g. Cole, 2015 [7], Malm, 2016 [8]), have all argued that long drought episodes "helped fuel the early discontent in Syria," which ultimately led to the country's downfall into conflict.

It's not a coincidence that immediately prior to the civil war in Syria, the country experienced its worst drought on record.

Former Secretary of State John Kerry

The combination of severe declines in rainfall and rising temperatures has caused the demise of agricultural fields, the advancement of desertification, and the mass migration of approximately 2 million people from rural to urban areas [9]. These climate-related environmental factors have contributed to the current civil strife and economic turmoil in Syria [10].

The Synthesis Report (SYR) of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) revealed that the Middle East as part of the Mediterranean Region has already observed progressive intensification of droughts (hydrologically, ecologically, and agriculturally). Furthermore, it is more likely to experience temperature hikes resulting in further aridity conditions and drought which increase the occurrence of wildfires. For a global warming of more than 2 degrees Celsius, these predicted effects are also accompanied by a large increase in sea level by mid-century [11].

Syria is not far from this scenario. Moreover, the susceptibility to drought is clearly anticipated. This is because Syria is already a conflict-fragile and stress-vulnerable system prior to the outbreak of the conflict there. With the upsurge in severity and frequency of droughts documented throughout Syria, high priority must be given in Syria's plans and policies to mitigate drought risks and controlling their cumulative effects. Nevertheless, rapid population increase, water shortages, land degradation and desertification, insufficient infrastructure, limited adaptation ability, and recent political crises have intensified and will intensify the consequences of drought in recent decades.

Of the nine countries rated as ‘very high risk’, Syria is the third highest at risk of drought [12].

Why does Syria need an urgent plan to mitigate drought spells?

The question is simple: to ensure food security.

Syrian Agriculture and Agrarian Reform Minister Mohamed Hassan Qatana's 21 May 2021 assertion that Syria is in an unparalleled drought becomes even more prominent and foreboding. According to Qatana [13],

“Syria has not seen such a drought in years. In previous years, drought was witnessed in one or two provinces only, while this year, all provinces have been affected, which severely impacted agriculture. Winter crops, namely wheat and barley, whose production is strategic, were very much affected, especially in rain-fed areas.”

The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 12.1 million Syrians (more than half the population), are in the grip of starvation. Another 2.9 million individuals are at danger of food insecurity, with a 52% rise in only one year [14]. Food insecurity had already reached alarming levels in 2021 and continued to deteriorate throughout 2022. In 2021 and 2022, Syria ranked 106 out of 113 countries assessed in the Global Food Security Index [15].

Does Syria have a drought mitigation plan?

The drought episode that occurred in Syria between 1999 and 2001 was the worst in the country's history and had a significant impact on the country's crop and livestock production. This, in turn, had a significant impact on the food security of a large portion of the population as incomes dropped sharply, particularly among the rural small farmers and herders [16,17].

Between 2004 and 2006, The United Nations Organization of Food and Agriculture (FAO) collaborated with the Syrian government to create an efficient early warning system for drought in Syria's rangelands [18]. The project's objectives were to train national staff in the Syrian Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform (MoAAR) on data collection, analysis, interpretation, and implementation, as well as to strengthen institutional capacity in drought early warning systems, with a focus on pastoralists and agro-pastoralists of the Syrian Steppe and its margins. In 2006, the Syrian project was finished. As a consequence, an early warning system office and a steering committee were established, as well as a set of drought indicators were identified.

Early warning systems were put in place to collect, organize, and process drought monitoring data (physical and social data); monthly drought bulletins have been produced on a regular basis in both English and Arabic since 2005; and Syria's technical capacity to operate a drought warning system was successfully developed [19].

The following are the significant shortcomings in Syrian drought management:

- Independent body or unit responsible for drought management.

- Standard management approach

- Regional sharing on drought information

- Weak coordination between various ministries and organizations

- Mitigation plans are mainly for emergencies and not updated regularly.

- Monitoring and real early warning system

Syria needs help in the following areas:

- Drought projection

- National drought strategy and action plan

- Adoption of standard approach

- Drought monitoring and early warning systems.

- Preparedness and mitigation action

- Emergency response and recovery measures

- Impact assessment

What does it lack?

The Syrian Plan is centered on the hazard and the social dimension is present in post-drought damage and loss practices. Going through the general guidelines of the relief directorate [20], we observe response plans of vulnerability and hazards school. Vulnerability is a crucial concept to consider when assessing the effects of a drought. It is strongly connected to food insecurity and may be described as the likelihood of an abrupt decrease in food surplus or consumption levels below the bare minimum required for existence. In severe drought, food insecurity intensifies as a result of a substantial reduction in food production / availability from both individual farms and the market, as well as an increase in income instability owing to a lack of work prospects and means of subsistence. Therefore, screening vulnerable communities, villages, and districts is vital for policymakers, especially the Drought Relief Department, in order to identify the target populations. It also helps in streamlining and preparing ahead for mitigation and adaptation measures.

In the context of Syria, the problem is exacerbated by the fact that the drought is perceived as a "crisis scenario" and a temporary issue, manages it as an isolated occurrence. Hence, after the rain is returned, it is typically not taken seriously; instead, it is treated as an event of more manageable disaster. Furthermore, Clear distinction between non-drought and drought is absent. At the household level, people would describe drought as a natural hazard beyond people's control at the household level. Both result in separate approaches and responses. They also have several negative repercussions and undesirable consequences. Therefore, they become more reliant and dependent on the government and demand aid and relief on a wider scale and for a longer period of time. Moreover, social resilience is weakened, leading to the perception that nothing else is conceivable, that there is no remedy that will enhance self-reliance. As a result, the government becomes confident, believing that its measures are in the best interests of the people and that it is performing all of the functions required of a welfare state. Droughts are seen differently by scientists, administrators, and politicians, yet their perspectives are not taken into account in state responses to droughts.

There is a tendency to exaggerate the severity of drought when compiling a Memorandum of Scarcity (MoS) for claiming funding from the government in order to create a case for greater subsidies from the authorities. For example, when agricultural areas are harmed, the damage should be more than 50% of the expected agricultural yield. More than 5% of the overall livestock population is least impacted by drought, resulting in more than 50% of the total cattle population's mortality.

Next Steps

The 'disaster pressure-and-release' model proposed by Wisner et al. (2004) is an important conceptualization because it incorporates knowledge from other fields, such as the 'hazards approach' and the food security literature (which emphasizes how social context shapes a more broadly defined vulnerability) to better predict and prepare for disasters [21]. Participatory techniques are used in assessments of vulnerability, with a focus on including local populations in the investigation of their susceptibility to pressures or dangers brought on by climate change. When the goal of the research is to alter the behavior of the people in relation to how they react to climate-related dangers, a participatory approach is acceptable as the method of inquiry.

Final Remarks

Drought monitoring and management necessitates more use of technology in advance forecast, monthly crop condition status, water body health, and so on. The knowledge acquired should also be made public for people's education and, as a result, the development of coping techniques.

Drought affects several regions of Syria every year. Yet, the state hasn’t so far succeeded in diagnosing the drought and devising a long-term strategy. Relief is now seen as the panacea for catastrophes. The following concerns are arising for policy development and action: (I) understanding the nature of drought, (ii) altering perception and reaction to drought, and (iii) shifting the focus from relief to drought mitigation.

References

[1] Selby J, Dahi OS, Fröhlich C, Hulme M. Climate change and the Syrian civil war revisited. Polit Geogr. 2017 Sep 1;60:232–44.

[2] Remarks by the President at the United States Coast Guard Academy Commencement.https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/05/20/remarks-president-united-states-coast-guard-academy-commencement

[3] Martin O'Malley: Climate change helped spark destabilization of Syria, rise of Islamic state. http://www.democracynow.org/2015/9/10/martin_omalley_climate_change_helped_spark

[4] Bernie Sanders: Yes, climate change is still our biggest national security threat. http://www.motherjones.com/environment/2015/11/bernie-sanders-climate-change-isis

[5] Charles: Syria's war linked to climate change. http://news.sky.com/story/1592373/charles-syrias-war-linked-to-climate-change

[6] Paolo Verme, et al.The welfare of Syrian refugees: Evidence from Jordan and Lebanon World Bank, Washington DC (2016).

[7] Juan Cole. Did ISIL arise partly because of climate change? http://www.thenation.com/article/did-isil-arise-partly-because-of-climate-change/

[8] Andreas Malm. Revolution in a warming world: Lessons from the Russian to the Syrian revolutions Gregory Albo, Leo Panitch (Eds.), Socialist register 2017: Rethinking revolutions, Monthly Review, London (2016), pp. 120-142

[9] How climate change paved the way to war in Syria [Internet]. Available from:https://amp.dw.com/en/how-climate-change-paved-the-way-to-war-in-syria/a-56711650

[10] Pax for Peace. “We fear more war, we fear more drought”: How climate and conflict are fragmenting rural Syria - Syrian Arab Republic. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/we-fear-more-war-we-fear-more-drought-how-climate-and-conflict-are

[11] IPCC. (2023) Climate change 2023. In: Hoesung Lee et al. (ed). Synthesis Report of The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Longer Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[12] Risks Associated to Climate and Environmental Changes in the Mediterranean Region.

[13] “Minister of Agriculture, Mohamed Hassan Qatana, for Sham FM” (in Arabic), Sham FM Facebook Page, May 21, 2021, https://web.facebook.com/radioshamfm/posts/3912435032143095?_rdc=1&_rdr

[14] World food Programme. Syria Emergency. https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/syria-emergency

[15] Global Food Security Index, The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022. Available at: https://cutt.ly/CKAcxUB

[16] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. (2004) Syrian Arab Republic: Capacity Building in Drought Early Warning System for the Syrian Rangelands. Syrian Project Document, TCP/SYR/3002 (T), May.

[17] Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). (2005). ESCWA Water

[18] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (2007) Capacity Building for a Drought Early Warning System in the Syrian Rangelands. Terminal Statement prepared for the 14 Government of Syria by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Cairo, Egypt, TCP/SYR/3002.

[19] ُEarly warning system for drought in Syria (syrdrt-sdews.net.sy)

[20] https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/syr186483.pdf

[21] Wisner, B, P Blaikie, T Cannon, and I Davis (eds.). 2004. At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters, 2nd ed. London, UK: Routledge.