It's here to stay! An acute water shortage is affecting the Syrian population.

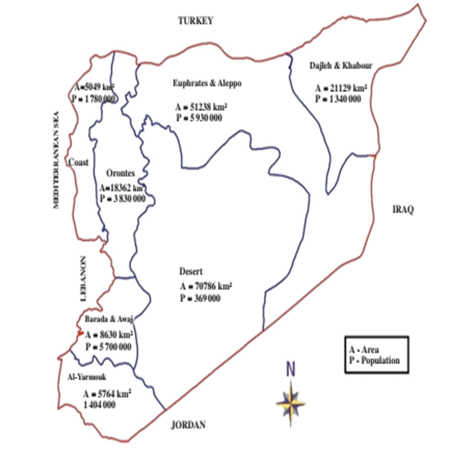

Syria is divided into seven distinct water basins, each with its unique climate, geology, and ecology: the Barada and Awaj, Al-Yarmouk, Orontes, Dajleh and Khabour, Euphrates and Aleppo, Desert, and Coast. Syria is home to 16 rivers and tributaries, 5 of which are shared with neighboring countries (Euphrates, Tigris, Orontes, Yarmouk and Khabeer al-Janoubi). Throughout the basins, both surface water and groundwater are available. There are eight major lakes, 160 surface dams, and 21 major rivers that are part of the area's surface water system. Some of the roughly 140 types of groundwater springs are dry now because of the ongoing drought. There are almost 40 percent of springs that have typical quantities of less than 15 l/s.

Syria’s water crisis in numbers

For more than a decade now, the conflict in Syria has ravaged the Syrian Populations, causing severe damage to water infrastructure. Millions of Syrians are struggling to get their hands on clean water since there is up to 40 percent less available today than there was a decade ago.

7th on a global risk index of 191 nations most vulnerable to a humanitarian or natural catastrophic event that might exhaust response capability, owing in part to the continuing war, which impedes appropriate preparatory measures.

3rd most likely among the nine countries at "very high risk" of drought.

5.5M People will have reduced access to drinking water

3M people will face reduced electricity availability

5M people have livelihoods that depend on agriculturalproduction, including 1.3 million in areas close to the Euphrates rive

The growing water shortage in Syria has devastating effects on the country's people and economy. Many years of severe drought plagued the nation (1999-2001 and 2006-2009), before to the conflict's start in the middle of March 2011.

Precipitation rates over 2020 decreased by 50-70% depending on the province.As a result, 80% of Syria’s rain-fed wheat fields in 2021, usually half of the country’s total wheat fields, were not planted due to the lack of rainfall in 2020. This left 40% of Syria’s total wheat fields lying fallow in 2021.

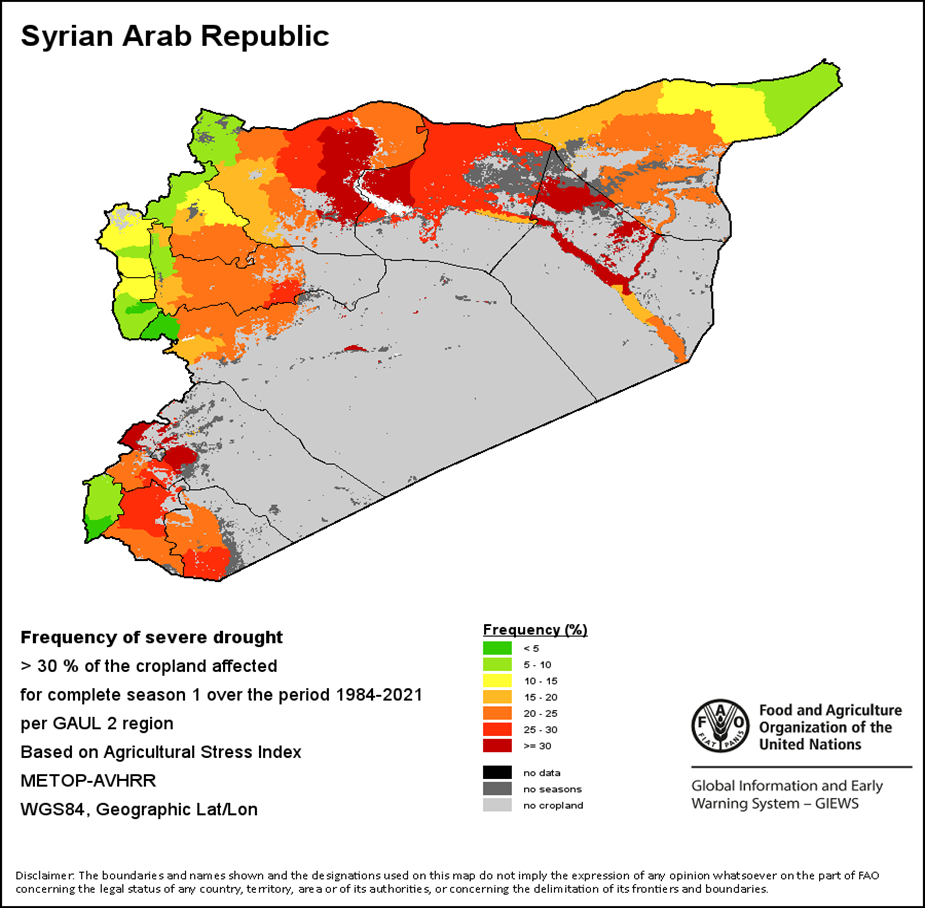

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization's Agricultural (FAO) Historic Drought Frequency over 1984-2021 as defined by the Agricultural Stress Index (ASI), illustrates the frequency of severe drought in places where 30% of cultivated land has been hampered by drought.

The Fertile Crescent: not anymore?

Syrian farmers have experienced consecutive years of poor harvests due to the country's severe drought. There is a general trend toward an increase in the severity of annual and seasonal droughts across all areas, which is correlating with an increase in the number of dry days during the wet season. Syria was ravaged by a severe drought between 2006 and 2009, with the worst years being 2007 and 2008, which led up to the outbreak of conflict in 2011. Because of this, many people in the media and in positions of power, such as former President Barack Obama and the current Secretary General of the United Nations António Guterres, have begun to speculate that climate change was not only responsible for the drought, but that it was also a significant factor in the subsequent civil war.

Euphrates water discharge continued to drop since 2005. 2021 marked the worst drought in Syria since 1953 as a result of the flow of the Euphrates River dropping to an all-time low in May 2021. This unprecedented and frightening drop in the water level of the Euphrates is alarming and threatening agricultural, home consumption, and energy generation in northern and eastern Syria since the Euphrates is the main supply of water for these uses.

Climate change was not the only cause of the 2011 conflict in Syria. Yet it also can't be denied as a contributor to why a once-thriving nation is now a parched, war-torn wasteland. As Syrians fear more war, they fear more drought. If the war is what drove Syrians out of their homes, drought and water scarcity are what preventing them from returning to their homes. Half of Syria's population faces hunger, are currently food insecure and a further 2.9 million are at risk of sliding into hunger.

More than 60% of the Syria's population, or 12.4 million people, were food insecure in 2020, 5.4 million more than in 2019. In 2021, the already dire food security scenario has worsened further. In 2023, 12.1 million people are food insecure and 2.7 million severely food insecure, according to the World Food Programme (WFP)

According to FAO (2021), the projected 1.05 million metric tons of wheat harvested in 2021 is a steep decline from the 2.8 million tons harvested in 2020 and represents only 25% of the 4.1 million metric tons harvested annually before the crisis. Over 260,000 metric tons of barley will be harvested in 2019 and 2020, representing around 10% of the record yields expected in those years.

What was once described to as the Fertile Crescent began its slow decline.

Another important challenge is how drought is shifting gender dynamics in northeast Syria. In the northeast of Syria, gender disparities have existed for a long time and are only becoming worse as a result of the drought; nevertheless, women are carrying the brunt of the burden both in the workforce and in the home. New research,designed by Mercy Corps and carried out by Triangle, has discovered that the lack of employment in the drought - stricken agriculture sector in the conflict regions of Al-Hassakeh and Ar-Raqqa is pushing women to seek other means to make ends meet.

A greater capacity for foresight is required, with more consideration given to the likelihood that such occurrences may recur often in the future. It is something that has been lacking, and not just in Syria. For this reason, the near future receives a lot more attention than the far future. These [long-term] concerns seem to me to be growing in significance.

So, kids, if you want to understand the politics of the Middle East today, study Arabic and Farsi, Hebrew and Turkish — but most of all, study environmental science.

Thomas L. Friedman [1]